By Jenna Kurtzweil

Bronze looks strange on a bison. I regarded the sculpture before me with a mixture of awe and skepticism as I awaited my parents outside the Prairie State Grill. The restaurant was the first pit stop along my family’s road trip from Illinois to Arizona, and its mascot — the bison — loomed large and lifelike before my 8-year-old eyes. Built on a rapidly developing stretch of grassland, the greasy eatery boasted prime real estate with a Wild West motif to match.

Given the historic association between American bison and western imagery, the restaurant’s choice of mascot was not surprising. And although the tavern’s guardian was majestic in its own statuary way, it was a far cry from the buffalo that thundered through my imagination, and that had once dominated this prairie: While the creature’s nose appeared dewy with moisture and its flanks were chiseled to mimic flesh and bone, its hooves remained welded to the platform on which it posed, and even the most persistent summer breeze couldn’t ruffle its metalwork hide. Something about seeing a bronze bison rather than its living counterpart upset me. A question haunted me on meeting the creature’s copper-plated gaze: How can we create restaurants dedicated to honoring bison while simultaneously destroying the creatures’ historic habitat?

An answer to this complex question demands an understanding of the bison’s checkered natural history. What, exactly, did the buffalo’s home look like? How did it feel to stand in this spot thousands of years ago, when bison reigned and the landscape wasn’t yet cloaked in concrete highways and fast food strip malls? I closed my eyes, pretending that the nearby traffic’s rumbling was the thundering of a thousand distant hooves. In my mind, I was on a journey to the distant past, a pre-industrial paradise of bison coexistence and ecological harmony.

Buffalo statue in Kearney, Neb. Credit: Wikipedia

But the bison’s role in the North American narrative is far muddier and more turbulent. While bison are largely perceived as quintessentially “American,” the species did not originate on the North American continent. DNA-based evidence uncovered in 2017 proves that the first bison migrated to North America 130,000 years ago via the Bering Land Bridge. Now fully submerged, the land bridge once connected East Asia to modern-day Alaska’s western coast.

Despite the variety of grazing megafauna already present in North America, bison thrived, increasing their range of distribution even as mammoths, ancient horses and giant sloths dwindled. Scientists today conjecture that the bison’s infiltration of the North American prairies is directly responsible — in conjunction with human involvement — for the extinction of prehistoric megafauna. For this reason, the bison’s establishment in the Americas is technically classified as an invasion rather than a migration.

Contrary to popular myth, the bison’s transformative impact on the pre-existing American ecosystem is outdone only by the wave of destruction brought by humans thousands of years later. Following their North American invasion, bison spent millennia evolving and honing the necessary traits to retain dominance. At the 15th century’s close — just as Columbus made his historic landfall — North America housed upward of 30 million bison, distributed across the Great Plains from Idaho to Pennsylvania and up into Canada’s southern provinces. Although bison have been hunted for about 12,000 years, the Native Americans’ largely sustainable practices posed no lasting threat to the species’ survival. Similarly, wolves and grizzlies (the bison’s only natural predators) never made a significant dent in the population. It’s not hard to believe, then, that North American bison remained stable for millennia, and herds numbering in the millions trekked their circular migration patterns — spending summers up north and moving south for the winter — year after year.

Back at the Prairie State Grill, the nearby rumble of traffic lulled for a moment, and the silence jarred me back to my bison-free reality. People chattered inside the restaurant, the grasses whispered and waved, but nothing thundered on the plains. As my family motored west, sightseeing opportunities became limited to vultures circling overhead, the occasional anomalous rock formation, freight trains streaking along distant tracks, and, of course, the free-range cattle that roamed the prairies in droves. I could hardly believe that scarcely two centuries prior, bison populated the plains just as abundantly as beef cattle do now.

Evidently, early colonizers shared my incredulity, and equated the vast multitudes of bison herds with what they believed to be a boundless supply of resources available in the American West. They wasted no time in tapping these supposedly infinite riches. Along with the harvesting of corn, tomatoes, and potatoes from the New World, bison were coveted by European traders for their hides, meat, and various organs harvested in their own right.

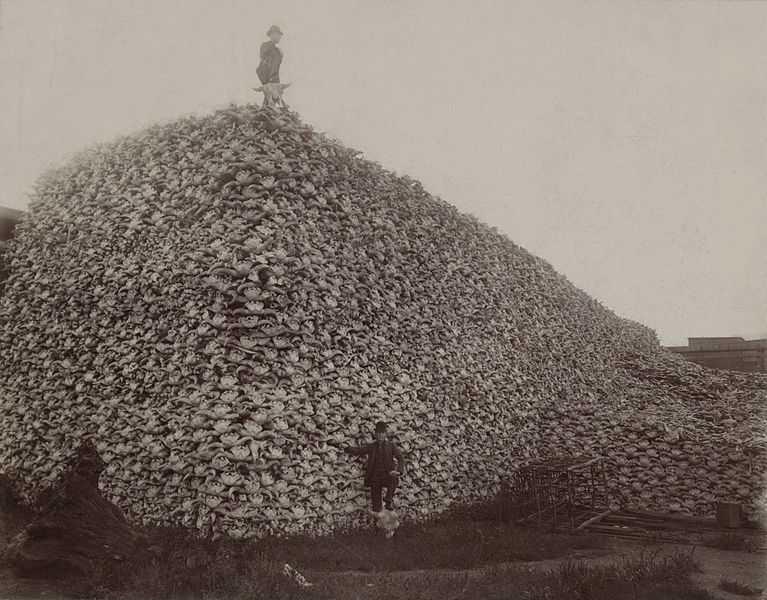

The Nature Conservancy chronicles the catastrophic fallout of the European bison trade, highlighting the fact that “unlike the Native Americans who utilized virtually all of the bison … white hunters became extravagant and wasteful. Taking only delicacies like the tongue, they left tons of meat and hide to rot.” The number of slaughtered bison during this period was so astronomical it was said that one could “walk … 100 miles along the Santa Fe railroad right-of-way by stepping from one bison carcass to another.”

Pile of bison skulls, 1870s. Credit: Wikipedia

Pile of bison skulls, 1870s. Credit: Wikipedia

American settlers embraced bison hunting with such zeal that its status quickly shifted from trading commodity to popular recreation. A particularly gruesome hunting exercise involved targeting herds from the windows of moving trains: the thousands of bison gratuitously slaughtered in this manner were never used in any way.

This bison-hunting mania was further fueled by widespread white antagonism toward Native American tribes, when the colonists’ fervor for sport-hunting converged with a genocidal agenda. By purging the tribes’ primary food source, settlers were able to weaken and exploit the Great Plains native communities.

Eventually, these horrifying tactics, which began as carelessness and ended in pointed aggression, took their toll: Over the course of the 19th century, a staggering 50 million bison were slaughtered. In the biologically brief span of a single century, 12 millennia of population growth unraveled, and the creature that had outlived woolly mammoths and saber-toothed tigers was brought to its knees by humans with barely a second thought. At the turn of the 20th century, fewer than 600 bison resided in the United States, just over half of the world’s total population. In 1889, the American public faced the alarming reality that more than 99 percent of the world’s bison population had been eliminated since the days of Columbus and, as is often the case, imminent catastrophe proved highly motivating.

For better or worse, the bison’s scrape with near-extinction acted as the catalyst that transformed Americans from primary predator to staunch defender, even worshiper, of the bison. Beginning with the termination of commercial bison hide shipments in 1889, activist groups rallied around the creature that had been recently been destroyed so mercilessly. The American Bison Society was founded in 1905 with the mission of reviving the species, and a bison adorned the back of the American nickel from 1913 to 1938. Through a mixture of activism, legislation, and privately and publicly managed herds, the population climbed to the tens of thousands by 1935. The American Bison Society, believing its mission accomplished, was promptly disbanded.

Bison remain symbolic of western freedom in the 21st century. Currently, the U.S. is home to roughly 350,000 bison split between private and public herds, the largest population since 1889. The year 2005 was noteworthy on multiple fronts as it witnessed the reincarnation of the American Bison Society as well as the revival of the American Bison Nickel, and in 2016, President Obama introduced legislation establishing bison as the national mammal.

As time goes on, bison continue to be beloved by the American public and protected by increasingly strict laws. However, they remain alienated from the symbols of freedom that the original European settlers associated them with. Bison roaming today’s grasslands differ from their ancestors in terms of lifestyle, ranging territory, and even genetic makeup. During the species’ most drastic population shortage in the late 19th century, they were often bred with cattle by ranchers looking to stabilize profit margins.

Today, American bison have escaped the threat of extinction, largely because of human intervention and population engineering. Humans continue to exert their godlike powers of selection, but with the intent to preserve rather than to profit.

Today, American bison have escaped the threat of extinction, largely because of human intervention and population engineering. Humans continue to exert their godlike powers of selection, but with the intent to preserve rather than to profit.

In Oklahoma’s Tallgrass Prairie Herd, for example, health and wellness data from the herd’s 2,500 bison are strictly monitored. While this close supervision is intended to protect, it showcases the meddlesome, even compulsive character of human intervention. It likewise prompts the unsettling question every environmentalist or mere bison-lover needs ask themselves: Is it that we humans can only operate in extremes — whipsawing from mass extinction of the bison to genetically optimized reintroduction in a few short generations — while ignoring all possibilities for retreat, to allow nature to take its course?

In the least flattering light, the bison’s reintroduction to the American prairie might be considered an egotistical effort to assuage our collective guilt and re-inhabit an idealized past. However, a less damning interpretation might acknowledge that in addition to providing us with a conservation “success story,” bison work wonders upon the American grassland. Bison are “selective grazers:” they gravitate toward dominant grasses, eating only those varieties that provide necessary nutrients, thus leaving less dominant species to flourish.

Additionally, bison are more sustainable grazers than cattle because they don’t eat grass completely to the ground, instead opting to shear off the top layer. This eating pattern allows the foliage’s lower levels to access more sunlight and results in the plain landscape’s close-cropped appearance. Early American explorer Meriwether Lewis commented to this effect in a journal entry dated July 17, 1806: “… the grass is naturally but short and at present has been rendered much more so by the graizing of the buffaloe, the whole face of the country as far as the eye can reach looks like a well shaved bowling green, in which immence and numerous herds of buffaloe were seen feeding … .”

This excerpt from the iconic diaries of Lewis and Clark not only acknowledges the bison’s ecological impact, but helps us imagine the historic prairie landscape with firsthand clarity. Perhaps the idealized image of bison herds blanketing green hills is not too far out of reach after all. The idea of reintroducing “buffaloe” to the grasslands in which they evolved is taking America by storm.

South Dakota’s Cheyenne River Ranch, run by Dan and Jill O’Brien, is a prime example of this agricultural shift. Having formerly managed beef cattle, the couple claims that their conversion to bison conserves resources that would otherwise have been devoted to keeping their herds well-fed and protected from the prairie’s harsh environment. While beef feedlots generate large quantities of chemical waste and non-organic contamination, the presence of bison on the prairie is virtually waste-free, proven to be sustainable through millennia of evolutionary refinement.

Speaking for a community determined to restore native creatures to native lands, Dan O’Brien passionately states that “what really needs to be out on the Great Plains…(are) the indigenous animals.” His powerful statement recalls the question that I agonized over at the Prairie State Grill: How can we justify displacing bison in order to construct bison-honoring restaurants, structures, and shrines? Bison imagery, it turns out, is not limited to restaurants at all, and can be found almost anywhere from the prairies across the plains: neon bison blaze down from billboards, while bison sculptures of every imaginable material — including bronze — populate antique stores. Even charming bison illustrations doodled cartoonishly on the fringes of menus are not uncommon, as my 8-year-old self can sheepishly report.

Bison, as at the Prairie State Grill, are both everywhere and nowhere. And how different, really, is the bronze bison from the herds roaming North America today, most of which wouldn’t exist without some form of human engineering? They are a form of “built bison,” sculpted not from bronze or copper, but from a collective human effort to restore that which was destroyed. Why do we do this? Is it a pure show of power, a deep yearning to return to the past, or a lingering unease about the fallout of American settlement? Perhaps it’s a combination of all three.

That said: Yes, the reintroduction of bison is an unparalleled victory of conservation, and the environment will be better for it. And yes, this reintroduction is being conducted entirely on our own terms. Celebration is definitely in order, but we must proceed with caution. After all, while bison might today appear docile to our uses, they are still descended from the heroic species that survived the Ice Age and outlived the woolly mammoths.

About the Author …

Jenna Kurtzweil is from Inverness, Ill. She is a senior English major at the University of Illinois. She hopes to pursue business or marketing writing in her future career, and she is passionate about the environmental and nonprofit sectors. This article was written for ESE 360, the introductory CEW course, in Spring 2018.

Jenna Kurtzweil is from Inverness, Ill. She is a senior English major at the University of Illinois. She hopes to pursue business or marketing writing in her future career, and she is passionate about the environmental and nonprofit sectors. This article was written for ESE 360, the introductory CEW course, in Spring 2018.

WORKS CITED

http://edmontonjournal.com/technology/science/new-fossils-genetic-tools-help-pinpoint-bison-migration-to-north-america https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/bison-vs-mammoths/# https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/13/science/bison-buffalo-north-america.html https://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/northamerica/unitedstates/oklahoma/howwework/bison-history.xml https://www.britannica.com/science/migration-animal/Mammals#ref497271 https://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/northamerica/unitedstates/oklahoma/howwework/bison-history.xml https://www.fws.gov/bisonrange/timeline.htm https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/a/american-bison/ https://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/northamerica/unitedstates/oklahoma/howwework/bison-history.xml https://www.fws.gov/bisonrange/timeline.htm https://www.usmint.gov/coins/coin-medal-programs/westward-journey-nickel-series/american-bison https://www.fws.gov/bisonrange/timeline.htm https://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/northamerica/unitedstates/oklahoma/howwework/bison-history.xml https://www.usmint.gov/coins/coin-medal-programs/westward-journey-nickel-series/american-bison https://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/northamerica/unitedstates/oklahoma/howwework/origins-of-the-tallgrass-prairie-preserve-bison-herd.xml http://thebisonlife.nebraskabison.com/2013/04/19/impact-of-bison-on-environmen/ https://lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu/item/lc.jrn.1806-07-17#lc.jrn.1806-07-17.01 https://www.patagoniaprovisions.com/pages/unbroken-ground