A major weather event in Miami floods out a film crew. Credit: Wikipedia

By David Marcus

When I stepped out of my taxi in Fort Lauderdale, my foot landed in a puddle.

“Sorry about that,” my driver said. “Should’ve let you out on the other side. This street always floods around this time.”

He meant Fall, when South Florida experiences what are called king tides, the highest tides of the year. When the cab drove off, it left a pool of muddy water in its wake, the ripples cascading into themselves like miniature tidal waves. What I took to be a puddle was actually a long, shallow pond of water covering half the road. After standing at the curb for a while trying to work out the best way to cross, I realized that I had no alternative: My feet were going to have to get wet. I looked up at the sky, then down to my submerged feet.

There is, I realized, no saving South Florida.

I flew to Fort Lauderdale from Chicago to visit my Aunt Linda, who’s resided in the city on and off for 10 years. Now she was living in an apartment a few miles down the coast. After I’d crossed the road, found the entrance to the beach, and made my way down the wooden path, I saw Linda waiting on the sand. She wore a black beach dress.

“Hey sweetie! How’re you doing?” she greeted me happily, and we got to catching up.

I sat down after a while and dug my feet into the warm sand. I stared out into the Atlantic. She noticed the soaking wet pair of shoes laid beside me and laughed, a little sadly.

“When I first started coming here 30 years ago, there was about 50 feet of beach between where we’re sitting and that ocean,” she said. At that moment I noticed the leanness of this beach, the gentleness of its slope into the impassive blue water. “Look at it now. It’s maybe 20 feet.”

That number — 20 feet! — hung like a hooked shark in the tropical air, converging in my mind with the flooded road behind me and the encroaching ocean ahead. Linda had been thinking it, too: The water was rising in Fort Lauderdale, just as it was across Florida and all up the Atlantic seaboard. A direct result of human reliance on fossil fuels, sea level rise is entirely predictable, and on track with scientific projections. Our production of greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide, prevents a portion of the sun’s heat from reflecting back into space and traps it in our planet’s atmosphere, thereby warming the Earth. This increase in temperature leads to the melting of ice sheets and glaciers. It also causes oceans to increase in size as they absorb the reflected heat, since water expands as it warms.

Harold Wanless

This thermal expansion, combined with land-based ice melt, is projected by the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to lead to a sea level rise of at least 3 feet by the end of this century. However, this projection, which assumes that the rate of ice melt won’t accelerate as the earth warms, is actually rather conservative. Other organizations forecast more perilous scenarios. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers — not exactly a radical organization — predicts a rise of up to 5 feet, while the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) projects up to 6.5 feet.

Some in the scientific community fear more extreme scenarios. Prominent Miami-based geologist Harold Wanless, for example, foresees a sea level rise of 10 feet or more by century’s end. No matter how successfully we reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, we are already locked into this sinking future, in which seas will continue to rise for centuries to come. According to Climate Central, a nonprofit research and news organization, even if we were to keep global temperature rise below 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, as the Paris Agreement specifies, sea levels may still rise 20 feet or more over the next several hundred years.

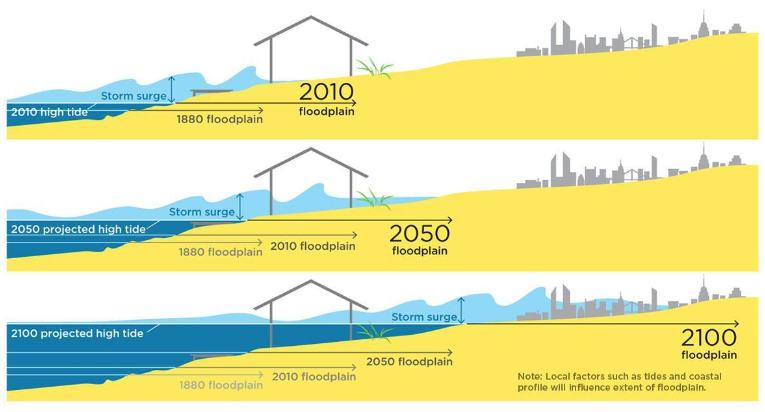

As sea levels rise, coastal cities will become more vulnerable to storm surges.

Credit: Union of Concerned Scientists 2015

In this dire scenario, nearly 300 U.S. cities will lose at least half of their homes by 2100, and 36 cities will be lost entirely. Yet even the lower-end projection of a 3-foot rise in sea level will wipe away coastal communities around the globe and inundate cities like Fort Lauderdale and Miami.

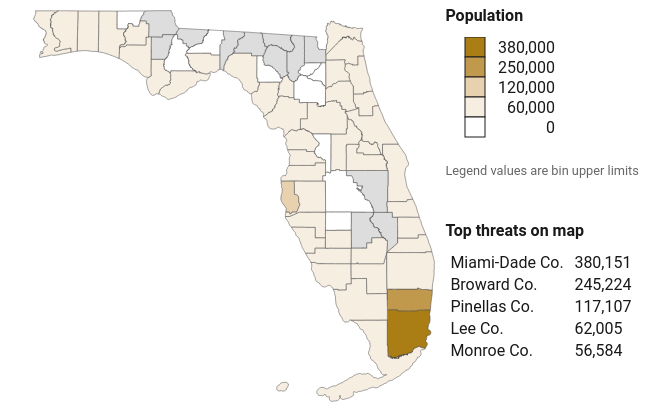

Long before those cities are submerged, however, they’ll experience chronic daily flooding. Puddles won’t just soak tourists’ shoes. Streets will be too flooded to drive through, and water will rise from beneath the ground. The Union of Concerned Scientists estimates that Miami-Dade County will suffer roughly 380 high-tide flooding events per year as soon as 2045. By that time, living in Miami, Fort Lauderdale, or anywhere else in South Florida will be nearly impossible.

For a city, state, and — by extension — country at such great risk, frighteningly little planning exists in the United States for this magnitude of sea level rise. Though the majority of Americans believe the climate is changing, many remain blind to the immediacy of the problem or expect that some god-sent technology will save us. We continue to live with our heads in the sand as the water inches up to our necks. In reality, there is no debate: South Florida is lost. The only question that remains is how we will plan for its demise.

With sea level rise, risks escalate quickly, and total inundation will be permanent. Credit: Climate Central

Denial

After an hour of hanging out at the beach, Linda and I walk back to her apartment.

“It’s a nice, old building I found with your grandma,” she said, as we walked along the same spot where my cab dropped me off. “Oh man — whooh!” Linda said, “Watch out for that that water! The neighbors are great; you’ll love it. I’ve got an air mattress all set up for you.”

The place was 15 minutes down that same road, the right side of which was lined with modest, four-story condos that looked like they were owned mostly by retirees. As we walked along, the public beaches on the left side became fenced off, and then replaced by massive, 20-story apartment buildings, each one more modern and lavish than the last. Soon, I could barely hear the ocean nearby, the breaking of the waves muffled by passing cars.

“They just finished construction on that one last year,” Linda noted, catching me staring at one particularly opulent development, a cylindrical, enormous building with an Aston Martin parked in front. “They’re always building something new around here.”

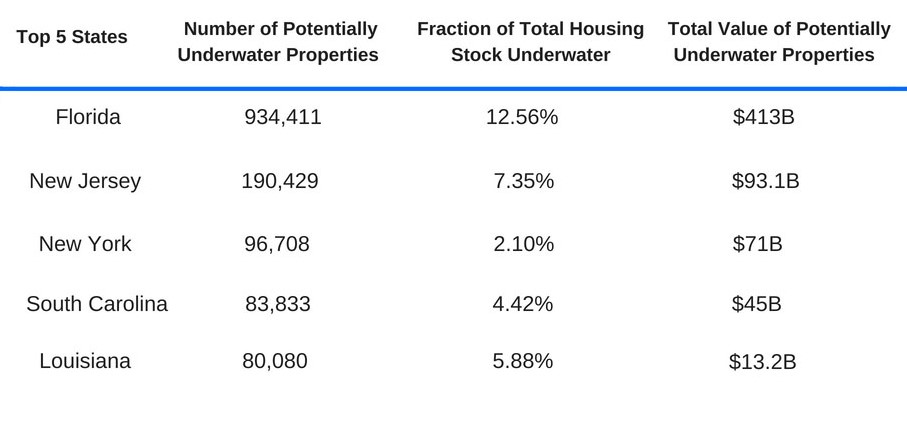

These days, Fort Lauderdale’s compact downtown is in the midst of a development boom. According to the city in 2017, almost 9,000 residential units and 900 new hotel rooms have been built, are being built, or have been approved for construction since 2012. All this despite the fact that nearly a million Florida homes worth more than $400 billion are at risk of being submerged by 2100.

Flooded beach homes on the Central Coast, 2005. Credit: Wikipedia

Flooded beach homes on the Central Coast, 2005. Credit: WikipediaApparently unconcerned with sea level rise, developers continue to build along Florida’s coastline, and as long as buyers remain hungry for properties, there’s no reason for the boom to end. Plus, developers have local governments on their side, which need high-end properties to help pay for defending shorelines.

This is especially the case in Miami. The more sizable and expensive condos there are in the area, the more taxes and fees Miami Beach can collect and use to fund anti-flooding projects — at least, that’s Miami’s half-baked plan to outbuild sea level rise. While the move makes sense for a state with no income tax, building more property to raise money to defend property is an absurd recipe for disaster. Yet this about marks the extent of the planning that Florida has done for sea level rise. Most of the time, developers and legislators keep busy pretending the beaches aren’t being swallowed by the sea.

“Last week I met a friend for lunch at this popular place, the Pelican Grand Reef Resort,” Linda says, “and there was barely any sand between where we were sitting and the water. Every one of these hotels and condos are losing their beaches. They wouldn’t have any beaches at all by now if they didn’t constantly bring in sand from offshore.”

By trying to bury their problems, developers mask the extent of the sea level rise predicament and do their best to keep up appearances. In doing so, they merely construct an increasingly lavish stage for the tragic final act of South Florida’s inundation.

The politicians presiding over Florida’s future promote a similar business-as-usual mindset. U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Florida, the former Chairman of the Subcommittee on Oceans, Atmosphere, Fisheries, and Coast Guard, has said that, since he is not a scientist, he is unqualified to have an opinion on humanity’s role in climate change. Florida Gov. Rick Scott, a fellow Republican, is equally skeptical about the human role in sea level rise, openly stating that he does not believe the climate is changing. Charlie Crist, Scott’s Democratic predecessor, made sea level rise a key issue during his tenure — and even called climate change one of the most important issues of the century.

But since the election of Scott, Florida has swung back to the denial camp. According to a report by the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting (and noted in sea level rise expert Orrin Pilkey’s book, Retreat from a Rising Sea), employees of the state’s Environmental Protection Agency have been ordered not to use the terms “climate change” or “global warming” in official communications. Though some forward-minded Floridians, such as South Miami Mayor Philip Stoddard, openly discuss the dangers facing their state, meaningful action is hard to achieve so long as the state and federal governments outright ignore the threat.

In a twisted way, one could argue that state politicians, as well as developers, are doing what’s best for Florida in the very short term. If they admit that beaches are disappearing and that roads are flooding, they acknowledge the existence of a threat that imperils the very future of their state. Property values will fall. Banks will stop writing mortgages. Condos will stop selling as the wealthy buy homes elsewhere. Residents will become anxious and start trickling out of the state, leaving behind unsellable homes. To avoid that eventuality for as long as possible, state politicians will likely turn a blind eye to sea level rise, ensuring that when South Florida can no longer ignore the catastrophe, its response will be haphazard and long overdue.

Total population below 5 feet in Florida by county. Credit: Climate Central

Yet Florida’s self-inflicted tragedy extends beyond the bounds of individual politicians and business interests. Climate change (and, by extension, sea level rise) has been called the ultimate wicked problem in that it endangers the entire planet while simultaneously exposing how poorly equipped we humans are, cognitively and politically, to manage a threat of precisely this complex, planetary character.

The consensus among climate advocates is that only long-term planning will save the global human community from the worst consequences of climate change. But the abbreviated timeframe of electoral politics that produces the likes of Rubio and Scott leads to nothing but short-term “solutions” to these long-term, systemic problems. Politicians promise to install more pumps, raise roads, and restore wetlands, even as the true extent of the threat goes unacknowledged and boom-time construction churns on mindlessly.

In reality, there is only one productive way forward: a frank discussion of the full gravity of the threat from the sea. Many Floridians will fight the hard truth of sea level rise by putting their faith in doomed-to-fail engineering projects. For instance, in response to frequently flooded streets, Miami Beach recently installed pumps that push water back into the Biscayne Bay, a lagoon south of Miami. The pumps manage to keep some neighborhoods dry during king tides; but streets still flood during rains.

The bigger problem is scale. While the pumps might work for Miami Beach, a city just eight square miles in size, in terms of energy expenditure, cost, and sheer feasibility, pumps could not possibly be implemented throughout South Florida. It would be akin to trying to hold out the entire ocean with pumps. Floridians might turn to other engineering solutions, such as sea walls. Designed to hold back the ocean and prevent shoreline erosion, a well-built wall will indeed fix the boundary between land and sea. Yet even the best constructed sea walls are not invincible. Over time, as waves erode the sand or soil anchoring a wall at its base, barriers become susceptible to collapse. Subsequently, one could imagine how even a perfectly constructed sea wall would need to be increased in height continuously as sea levels rise, and would cave under its own weight eventually.

Regardless, sea walls will probably never be constructed along Florida’s coast for the simple reason that residents will never consent to lose their beaches. Beaches are the hallmark of Florida; they provide residents with quick access to the ocean and bring in billions of dollars worth of tourism every year. They are the very essence of Florida life, and most residents would sooner leave than lose their beaches to giant, costly, and ugly sea walls.

Danger from Below

Even if one continuous, indestructible sea wall were to be constructed along the entire 1,350-mile-long Florida coastline . . . Even if the state were outfitted with an army of dikes, water pumps, levees and walls…Florida still cannot be saved from the rising tide.

The doom of the Sunshine State is sealed by two words: porous limestone.

Picture a 40-foot-thick layer of sponge made of stone beneath the ground. That is what underlies most of South Florida, including Miami and Fort Lauderdale. The remains of sand grains and the skeletons of tiny plant-like animals deposited in shallow water 125,000 years ago, Florida’s limestone is very porous, i.e., full of little holes. This means that fluids can move through the many interconnected pore spaces with ease. In fact, the limestone beneath South Florida is so permeable that the water levels of some ponds in Miami actually rise and fall in concert with offshore tides.

The geological significance of this limestone to South Florida’s future cannot be overstated. Like a scene from an apocalyptic movie, the water will literally come up from underground. Because of the certainty of this inundation, Pilkey writes in Retreat from a Rising Sea, Miami is more threatened by sea level rise than any other major city in the United States. Its greater metropolitan area has a population of 5.5 million, billions of dollars worth of real estate, and hundreds of schools, hospitals, power plants (two of which are nuclear), sewage plants, landfills, and hazardous material sites that stand at risk of flooding.

Even before the Atlantic overtakes the city completely, freshwater flooding will become an increasingly chronic problem for residents. Built on lands that were formerly Everglades, South Florida is as flat as it is low, and would flood after rainfall events if not for the 2,300 miles of canals that redirect floodwater to the Everglades and the ocean. When the canal system was implemented half a century ago, its builders quickly realized the potential for storm surges to push seawater up the canals into the interior of the state. Consequently, flood control gates were built to prevent the salinization of freshwater sources. The logic went that the gates could be closed whenever a storm threatened in order to halt saltwater intrusion. When closed, the gates do just that, but they also stop the canals from draining rainwater and have the potential to flood the region from within. In the years since the floodgates were constructed, local sea level has risen by 5 to 8 inches and multiple gates have become unable to discharge stormwater runoff during high tides

Top five states with coastal properties values threatened by sea-level rise.

Credit: Zillow and NOAA

According to Leonard Berry, Director of the Florida Center for Environmental Studies, just 6 more inches of sea level rise may cripple nearly half of South Florida’s flood control capacity. As sea level continues to rise and inundate land, Pilkey concludes that more floodgates and, eventually, the canal system itself, will be rendered useless. Sea water will reverse the flow of the storm drains, and there will be nowhere for freshwater, or sewage for that matter, to go.

This flow reversal has already begun in Miami, where water often pours from the storm drains onto the street when tides are high.

“Last time I was in Miami a year ago,” Linda told me as we strolled along the beach, “I saw streets flooded outside people’s homes. There wasn’t even a cloud in the sky — it was warm and sunny, and the streets were so flooded you had to wear rain boots to walk through them.”

According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, residents of Miami Beach can expect to experience flooding more than 230 times a year within two to three decades. Because of all that backed-up sewage, the floodwaters that will spill from storm drains into the streets are going to give off a strong smell of human waste. When freshwater flooding isn’t a problem, obtaining freshwater for consumption will be. As sea level rises, salinization will deplete South Florida’s freshwater supply, which is stored in the form of groundwater and drawn from the Biscayne aquifer.

In fact, saltwater has already contaminated much of the groundwater along the state’s coast. Because the sea has intruded into its freshwater wells, Hallandale Beach, a city north of Miami, is moving its entire drinking water supply westward. Pilkey thinks more wells could theoretically be relocated farther away from the ocean, but it would only be a matter of time before those sites become salinated, too. As the end of the Florida Dream draws near, porous limestone, a soon-to-be ineffective canal and floodgate system, and salinated groundwater will combine to render Miami and its surrounds uninhabitable. This doesn’t even take into account the increased intensity of storms and higher storm surges that will result from rising seas. By the midpoint of this century, if not sooner, Miami, Fort Lauderdale, and every town in South Florida will be a salty, wet marsh on its way to being swallowed by the ocean entirely. Miami mayor Stoddard puts the situation bluntly:

“Another foot of sea-level rise will be enough to bring saltwater into our freshwater supplies and our sewage system….You won’t be able to flush away your sewage and taps will no longer provide homes with fresh water. Then you will find you will no longer be able to get flood insurance for your home. Land and property values will plummet and people will start to leave. Places like South Miami will no longer be able to raise enough taxes to run our neighbourhoods. Where will we find the money to fund police to protect us or fire services to tackle house fires? Will there even be enough water pressure for their fire hoses? It takes us into all sorts of post-apocalyptic scenarios. And that is only with a 1-foot sea level rise. It makes one thing clear, though: Mayhem is coming.”

Porous Futures

South Florida is doomed; there is no saving it. The only productive discussions going forward will be discussions of exodus, of getting people out of harm’s way and dismantling sensitive infrastructure (such as the Turkey Point nuclear plant) as cleanly as possible. Luckily, the U.S. has one major resource that most nations vulnerable to rising seas do not: abundant land to retreat to. So-called “managed retreat,” the policy supported by geologists like Harold Wanless, represents the best option for South Florida residents.

Retreat, a barely reassuring euphemism for abandonment, would obviously be a hard pill to swallow, but it’s better than the alternative: sudden mass evacuation once the water overwhelms the state or housing markets collapse. Picture the humanitarian disaster of Hurricane Katrina multiplied a thousand times: the submerging of homes, missing loved ones, ways of life and livelihoods destroyed, life savings lost in rotting and unsellable homes, followed by a mass refugee exodus that makes the Dust Bowl look like a day hike.

If Floridians allow sudden abandonment to become reality, this is what lies in store. It will be up to them to decide if their migration will be coordinated and orderly, or hellish and chaotic — if they will plan for the future sensibly, or stick to their guns until the water rises to their doorsteps. Theoretically, much of the damage rising seas will cause can be averted simply by acknowledging and planning for the future. If Floridians can formulate an organized plan of retreat, they will spare themselves the potentially apocalyptic alternative.

Blue sky flooding in downtown Miami. Credit: Wikipedia

Florida’s government, in cooperation with the federal government, has the ability to adapt to the threat of rising seas. The most straightforward way to do so would be to offer South Florida’s nearly seven million permanent residents financial incentive to move away from the coast. But a buyout on any kind of meaningful scale would require an immense amount of funding, as well as bipartisan support, both of which make the prospects of such a project unlikely to say the least.

If it can’t incentivize its citizens to leave, then the least Florida can do is educate its citizens about the extent of the problem facing their state. However, based on the state’s current political stance on climate change, it seems unlikely that it will do so. This dismal outlook merely points toward a deeper structural issue: Our economy and urban planning schemes are not designed to accommodate mass retreat scenarios (up until now, of course, they haven’t had to be).

Subsequently, it will probably be up to Floridians to plan for their own futures. If a mass buyout were to be floated, Americans beyond Florida would have to ask themselves if they would be willing to pay for such a program, or if they would rather let economics play itself out. Policies of managed retreat, massive federal programs to help the imperiled … these must be the talking points in an age of rising seas, as the waters will only continue to increase for centuries to come.

If the higher-end estimates of geologists like Wanless become reality, and sea levels rise by 10 feet or more in the next century, we face a global human catastrophe unlike anything the world has ever seen. It won’t just be Miami and Fort Lauderdale. It will be New York, it will be Boston, San Francisco, Baltimore, and Charleston; it’ll be Osaka, Rio, Alexandria, Tokyo, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Bangkok, and Jakarta — hundreds of cities across the globe, every one of them overtaken by the ever-rising sea.

Independent research group Climate Central estimates that at least 150 million people currently live on land that will either be exposed to chronic flooding or submerged by the year 2100, and that number will only increase. How will global society absorb what will become the greatest involuntary mass migration in human history? The point of this question is not to terrify everyone, but rather to generate constructive discussion about the future that awaits us.

We are heading into a world in which humanity will face challenges greater and more complex than any before, and we in the U.S. must ask ourselves difficult questions about what kind of country we want to be in that future. Will we be a country that plans ahead responsibly and supports its citizens, or a country that reels from disaster to disaster and forsakes those in need?

This is not a hypothetical. This is a call to action. The tide IS rising. South Floridians must be the first to decide what to do about it. Hopefully, their actions will serve as a model. If not, well, you’ll see it on the news.

By the time we arrive at Linda’s apartment, it has started raining. It is one of those calm-inducing, powerful rains that happen only in Florida. We spend the afternoon sitting around the table, talking about things, talking about family, as raindrops batter the thick green leaves beyond the windows. I can hear someone on the television in the other room. Probably Rubio talking politics, I think, or the Weather Channel forecasting rain. Tourists are probably holed up in hotel rooms nearby, the families disagreeable, wishing for sun rather than clouds. I’m sitting in a chair on the second floor of a condominium that will not survive a 30-year mortgage when, unexpectedly, there’s a knock on the door.

“The neighbors,” Linda announces. “Please, let them in.”

They’re nice people, as she promised they would be, and we strike up a lively conversation. “Oh, this place is wonderful,” they assure me — “and so close to the beach!”

About the Author …

David Marcus is an English major from Chicago. Marcus strives to use the power of writing to make this Earth a kinder and more compassionate place. “The Rising Tide” was researched and written for ESE 498, the CEW capstone course, in Spring 2018.

David Marcus is an English major from Chicago. Marcus strives to use the power of writing to make this Earth a kinder and more compassionate place. “The Rising Tide” was researched and written for ESE 498, the CEW capstone course, in Spring 2018.

WORKS CITED

https://www.livescience.com/60648-king-tides-flood-florida-streets.html

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/12/21/the-siege-of-miami

http://www.climatecentral.org/news/sea-levels-rise-20-feet-19211

https://www.zillow.com/research/climate-change-underwater-homes-12890/

http://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/broward/article181576881.html

http://www.fortlauderdale.gov/home/showdocument?id=20045 https://www.zillow.com/research/climate-change-underwater-homes-12890/

Pilkey, O.H., et al. Retreat from a Rising Sea, 36-37. Columbia UP, 2016

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hnUgvBQPuUo

http://www.businessinsider.com/miami-floods-sea-level-rise-solutions-2018-4 http://www.climatetechwiki.org/content/seawalls

Pilkey, O.H., et al. Retreat from a Rising Sea, 35. Columbia UP, 2016

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/12/21/the-siege-of-miami

Pilkey, O.H., et al. Retreat from a Rising Sea, 35. Columbia UP, 2016

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/event-tracker/king-tides-cause-flooding-florida-fall-2017

Pilkey, O.H., et al. Retreat from a Rising Sea, 32. Columbia UP, 2016

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/event-tracker/king-tides-cause-flooding-florida-fall-2017

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/12/21/the-siege-of-miami

Pilkey, O.H., et al. Retreat from a Rising Sea, 36. Columbia UP, 2016

http://news.mit.edu/2017/kerry-emanuel-hurricanes-are-taste-future-0921

Pilkey, O.H., et al. Retreat from a Rising Sea, 39. Columbia UP, 2016

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/nov/03/miami-shanghai-3c-warming-cities-underwater

http://www.climatecentral.org/news/sea-levels-rise-20-feet-19211