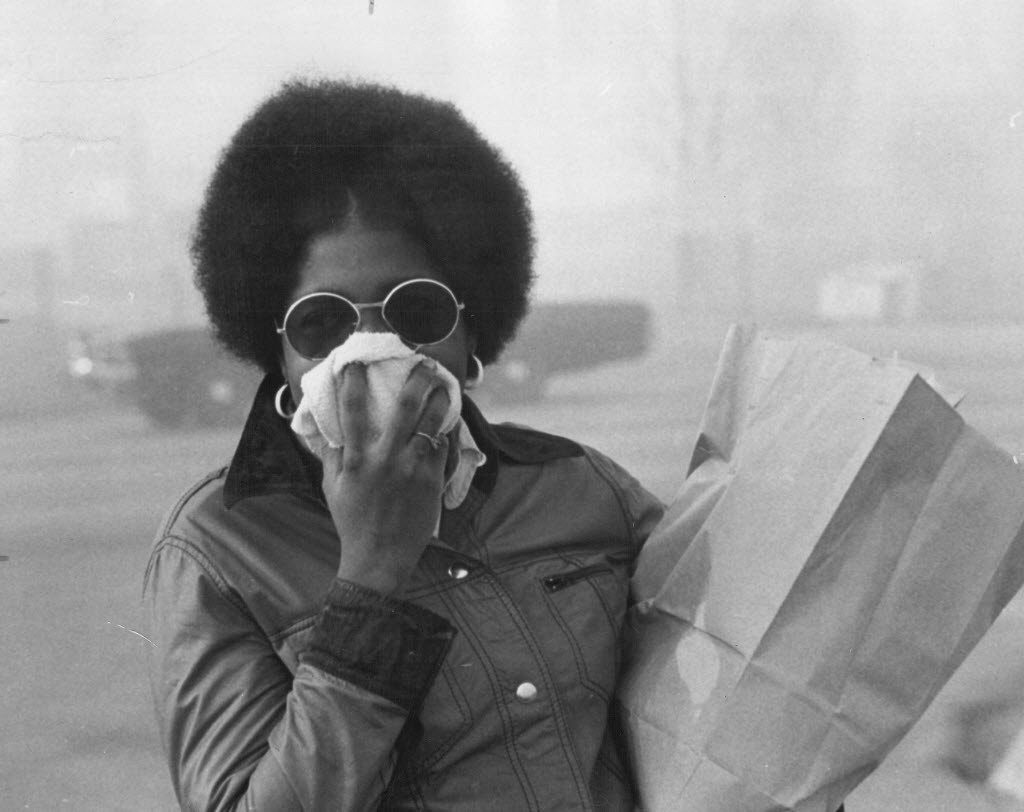

A Chicago resident protects herself from noxious fumes. Credit: Sun-Times Media

By Lisen Holmström

To get to Altgeld Gardens, I take the Chicago Transit Authority’s Red Line to 95th Street and then Bus 34 toward 131st and Ellis. It takes about 90 minutes, but I don’t mind. What surrounds the public housing community in Southeast Chicago interests me just as much as Altgeld Gardens itself. I’m heading there to see Cheryl Johnson, daughter of “The Mother of Environmental Justice,” Hazel Johnson. She has agreed to meet with me in the office of the grassroots activist organization her mother founded in the late 1970s.

As the bus closes in on my final stop, the scenery changes from residential to industrial. Looking out the window to the left, I see the Calumet Water Reclamation Plant, a water treatment facility that has been in operation since 1922. Wastewater and stormwater from Chicago flows here through enormous pipes right below my bus seat. About 256 million gallons of dirty wastewater are treated here, out of Chicago’s daily output of 1.4 billion, and then discharged into Little Calumet River. The river carries the discharge right by Altgeld Gardens.

My eyes swivel from the rectangular structures of the reclamation plant to the other side of Little Calumet River, where a huge dystopian industrial plant sits, rusted and abandoned. I try to find it on the map on my phone, and although it’s as obvious on the satellite image as it is in real life, there’s no name on the map. But the turn in the river reveals the unmistakable peninsula it sits on: this is the sprawling Acme Steel Mill that operated from 1918 until the company filed for bankruptcy in 2001.

I keep searching the map on my phone to see what other old factories are located in this area: industrial plants, recycling center, landfills. But then there’s also open green space, blue water, and a forest reserve. Suddenly we leave the factories behind and enter a housing complex, far too well-structured and uniform not to be built all at the same time. This is Altgeld Gardens, where I get off the bus.

Pretty much immediately, I get lost. I’m not the only one this happens to; I’ve heard residents describe this area as a labyrinth. Apparently, even police and firemen have trouble finding the right unit when they get a call. It’s a weekday, right before noon, and the area is completely empty. All the houses look the same: two-story brick buildings with a grill and some chairs outside every entrance. After a while I can’t tell if I’ve seen that playground before, or if this is another one. A helicopter flies by, and as it’s the first sound I hear in a while, it makes the area feel even emptier. Almost tranquil. The old factories and landfills emit no sound. But I can smell them. I remember reading a quote by Hazel Johnson where she describes the Altgeld air as three distinct smells: a sulfur smell, a chemical smell, and an odor like corpses.

The memorial wall in Altgeld Gardens. Credit: Lisen Holmström

The memorial wall in Altgeld Gardens. Credit: Lisen Holmström

I arrive at what I think is the center of Altgeld Gardens, but what makes me unsure is that it’s lacking the shopfronts that in my mind constitute an urban center: stores, restaurants, banks, cafés, perhaps some kind of transit station. Or at least people moving around. A car finally arrives, and a young girl yells goodbye and waves to her dad as she quickly hops out of the car and skips through a short breezeway toward her school. As she disappears, I recognize the breezeway from my internet research: It’s the yellow brick memorial wall.

While famous walls don’t tend to symbolize positive things, not all symbolize death as bluntly as this one. In addition to a somewhat scratched off layer of yellow paint, the wall is covered with big black letters. They make up names of Altgeld Gardens’ dead, those who died long before their time. Some of the deaths were due to violence, but most belong to the housing complex’s toxic environmental legacy unearthed by Hazel Johnson. And the names are spreading, like cancer. They no longer just cover the yellow-painted parts of the wall; they’ve worked their way all the way up to the ceiling. As I look at it, I wonder if it should be called “the Wall of Environmental Deaths.”

When I arrive at People for Community Recovery (PCR), Cheryl Johnson isn’t there, but some of the other members let me in. The office is now located in one of the two-story apartment buildings, and as there is no sign outside, I rely on locals to show me the place. The walls inside are filled with research posters with infographics about pollution, as well as awards and pictures of Hazel Johnson that keep me busy for a while.

When Cheryl gets there, I ask her why a public housing complex was ever built in such a heavily industrialized area. Cheryl and I sit down at a table filled with pile on pile of research on air pollution in the area. Cheryl is the current Executive Director of PCR, taking over after her mother passed away in 2011.

“The city of Chicago knew the land was contaminated when Altgeld Gardens was built,” she says. “But there was a great need for housing, particularly for black veterans.”

Altgeld Gardens was built in the 1940s to house black veterans coming back from World War II. It was one of America’s first public housing projects and might still today be one of the best — at least according to a narrow definition of urban planning that ignores the environment. Hazel Johnson was born in New Orleans in 1935 and quit high school after her sophomore year. She worked at a produce company when she met her husband John at 17, and they had seven children together.

The Johnsons moved to Chicago and Altgeld Gardens in 1962, when it opened to renters without veteran status. They had visited Altgeld Gardens before: Hazel’s brother-in-law, who was a veteran, had been living there for some time. She’d fallen in love with the place. Although it was isolated from other residential areas by highways and industrial plants, it was also peaceful, green and serene, close to water and a lot of open space for the kids to run around in. The seven kids could even stumble upon wildlife such as deer and coyotes close by the new home. They signed the lease, and Hazel was thrilled.

The abandoned Acme Steel Plant on the Little Calumet River, adjacent to Altgeld Gardens. Credit: Ken Lund

The abandoned Acme Steel Plant on the Little Calumet River, adjacent to Altgeld Gardens. Credit: Ken Lund

But, as it turned out, this public housing paradise had dark secrets buried beneath it. Long before architects Hans Naess and Charles Murphy put pen to paper to draw up Altgeld Gardens in the early 1940s, the area had been a dumping ground for toxic sludge waste from the Pullman Palace Car Company for decades. With all the waste facilities and heavy industry, the ground where the architects turned the first sod was heavily polluted. John Johnson didn’t end up living in Altgeld Gardens for very long. In 1969, lung cancer caught up with him, and he passed away at age 41. Cancer, as well as asthma and respiratory problems, seemed to be catching up with many of the neighbors in the area. It had become normal in Altgeld to have family members with a number of health problems.

But there were other issues to deal with in the community. Roofs were leaking, paint was peeling off, and water pressure was little to none in most houses. Hazel, now a widow with seven kids, founded the group People for Community Recovery in 1979. She wanted to organize the community to bring up quality-of-life issues and question the Chicago Housing Authority’s (CHA) poor maintenance of the buildings. It was so unreasonably hard to get anything, even a broken window, fixed. However, it didn’t take long for the health issues to come knocking again. And this time they would be impossible to ignore.

A local case including four mothers and four little baby girls was brought to Hazel’s attention.

“The four mothers had all grown up in Altgeld and lived almost next door to each other,” Cheryl tells me as she reaches for a cardboard box to show me that the babies were so tiny they could’ve fit in it. The babies had all been diagnosed with multiple forms of cancer. “And nobody was talking about it. You know, cancer during that period of time was shameful; people kept it hidden. Instead of understanding that when you have a cluster of same types of cancer in a defined area, it’s signifying that something is going on.”

None of the little girls would live to see their seventh birthday. This wasn’t happening in every Chicago neighborhood — that was for sure. Sitting at home watching television one night in the late 1970s, Hazel started connecting the dots. The news anchor was talking about a new study by the Illinois Department of Public Health. It showed that the cancer rate in South Side Chicago was a lot higher than average. And on the South Side, Altgeld Gardens, together with Calumet City, were the two areas that had significantly more cancer cases than the rest of the city.

Hazel picked up the phone and called everyone she could think of who might have answers. She called authorities in Chicago, and then started calling Washington, D.C. She contacted academics and activists. This was what she found out: She was living in an area surrounded by 50 documented old landfills as well as 382 polluting sources, including Sherwin-Williams Paint Co., PMC Specialty, Ford Motor Co., the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Chicago, Waste Management Inc., and many others, that were leaking toxins into the ground, water, and air in her community. Once Hazel learned  this fatal fact, Altgeld Gardens was no longer paradise to her. Her neighborhood was blighted. She would come to call it “The Toxic Doughnut.”

this fatal fact, Altgeld Gardens was no longer paradise to her. Her neighborhood was blighted. She would come to call it “The Toxic Doughnut.”

People for Community Recovery was a pioneering environmental justice organization. United with neighboring areas such as Hegewich, Pullman, and Calumet City, hundreds of people protested against a Waste Management hazardous landfill in 1989. The landfill had already been suspected to leak toxins, and now the company wanted to expand with a new treatment facility. After the media had all left the rally, Waste Management had the protesters arrested. But they got out of jail and went on to protest a local incinerator.

Hazardous chemicals were even closer than Hazel Johnson first thought. Not just the air, water, and land were contaminated, but the houses themselves were toxic. Lead and asbestos lined their homes, in the peeling paint on the walls and the insulation inside them. The lead paint tasted sweet, like lemon drops, and the kids would eat it. Asbestos had been commonly used in insulation and is believed to have caused thousands of deaths in the United States.

The activists in Altgeld Gardens had now teamed up with a young community organizer named Barack Obama, just graduated from Columbia University. They pressured the CHA — which first denied an asbestos problem — to finally pay to remove it from all the houses. Then another shoe dropped. Hazel learned that barrels of polychlorinated biphenyl (commonly known as PCB), used as lubricant in old electrical transformers, had been illegally dumped in a storage unit in Altgeld Gardens in the 1970s.

“It was an undercover deal; someone got kickbacks to allow them to dump it here. That same person was also living out here, so he didn’t know what he was doing. He eventually died from cancer, too,” Cheryl says. It took about 30 years and a class-action lawsuit against the CHA to get the area cleaned up. “And if you ask us, as an environmental group, it’s not really clean.”

Cheryl Johnson is continuing the fight. Credit: PCR

Cheryl Johnson is continuing the fight. Credit: PCR

People for Community Recovery started to collect data on health trends in the community, hoping to be able to prove that the health problems were caused by the pollution. Their health surveys showed that 90 percent of the residents had respiratory troubles, skin rashes, burning eyes, and other ailments commonly connected to air pollution. And then there were the continuing sky-high cancer rates. But environmental links to cancer are not straightforward to prove. Neither, in Altgeld Gardens, was proving accountability.

“It’s difficult in this area when you have over 300 polluting entities” Cheryl explains. “If you connect a chemical to one industry, he’s going to say, ‘No, that isn’t mine, that came from somebody else; we both use the same chemical.’ ”

The buck stops nowhere. Even though a lot of research has shown that zip codes can be linked to increased mortality risks, there is a lack of consensus about what it is about a neighborhood that specifically effects resident health, and in what ways. Researchers have pointed to different factors, such as access to fresh food, proximity to health care, and social marginalization, in addition to environmental dangers.

Meanwhile, the dangers of the Toxic Doughnut also seem to be different depending on who you ask. When PCR and Greenpeace tested the drainpipes of a nearby landfills, they found excessively high levels of carcinogenic and toxic chemicals in the Calumet River. But when the Environmental Protection Agency conducted a soil test in 1996, after years of pressure from the Altgeld community, it concluded (based on “limited information”) that “no apparent health hazard exists from exposure to the surface soil contamination detected in Altgeld Gardens.”

Even without conclusive studies, PCR members have always been sure that the large amounts of chemicals measured in Altgeld Gardens and surrounding areas can be deadly. As Hazel once wrote: “We have to fight for our children. We have educated ourselves on environmental issues and the health threats from nearby polluting industry. We have not waited for government to come in and determine the cause of our illness. We may not have Ph.D. degrees, but we are the experts on our community.”

She was right. And as it turned out, Altgeld Gardens wasn’t the only minority community experiencing the burden of waste-dumping. Soon, the environmental justice movement, on the Altgeld Gardens model, had spread nationwide.

Altgeld Gardens in better times. A street parade in the early 1950s.

Credit: Chicago Housing Authority

From the beginning, Altgeld Gardens was an overwhelmingly black community, with 62 percent of residents living below the poverty line. In Chicago, one of the most segregated cities in the U.S., the hard work by white segregationists had shaped the city to make dumping toxins on minority communities possible. Karl Grossman writes in his book Environmental Racism that without racist zoning laws in the 1920s, a housing complex like Altgeld Gardens would never have been built in such a heavily polluted area.

“You will not have this happening in an affluent white community,” Cheryl insists. “If you are poor, you get dumped on. You get the burden of the pollutants in your neighborhood because of the fact that you are apolitical. You don’t have that voice to make policy change, or to make enforcement happen that is already on the book to protect public health. But race is one of the common denominators in this.”

Hazel Johnson worked tirelessly to raise the voices of the poor. During the ’60s and ’70s the environmental movement in the U.S. had been a mainly white and middle-class movement focused on preserving wildlife. She joined anyway, but was usually the only minority representative at the conferences and gatherings. Her perspective was different: She was concerned with human health issues in relation to the environmental ones. She wouldn’t be alone for long, as the environmental justice movement grew rapidly.

The movement doesn’t have one recognized starting point. Complaints from minority communities about unfair environmental burdens had already been going on for decades, but during the 1980s these separate complaints merged into a movement. Often mentioned as the first big event was a massive protest against a landfill for illegally dumped PCB-contaminated soil. The landfill was to be placed in a small black community in Warren County, N.C., and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) decided to organize against the siting. Although the protest — during which 500 protesters were arrested — was unsuccessful in preventing the landfill, the similarities with the situation in Altgeld Gardens and other minority communities was obvious, and a nationwide network of environmental justice organizations started forming. In 1983, the General Accounting Office found in a study that African Americans was the majority population in three out of four communities in the Southeast where toxic waste facilities had been placed. It would take until the 1990s, however, for the federal government to recognize environmental justice as a political issue and human right. When Hazel Johnson attended the first National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1992 in Washington, D.C., she was officially named “The Mother of Environmental Justice.”

Bill Clinton signs the landmark 1994 executive order on environmental justice. Hazel Johnson is standing third from right. Credit: PCR

“My mother had a way of reaching people’s hearts, telling the same story over and over and over again. Didn’t change it at all,” Cheryl says. “But a lot of people felt her, and they were really amazed that a widow with seven kids, living in public housing, was talking about environmental issues. And being a black woman. That was just unheard of.”

Two years later, Hazel Johnson stood next to President Clinton’s desk in the Oval Office as he signed the Executive Order 12898: “Federal Action to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations.” The photograph of Clinton signing the document is one of the pictures hanging on the wall of the office in Altgeld Gardens. For Hazel, it was a moment of official recognition in a long career spent challenging officialdom.

Cheryl gets a phone call and excuses herself from the interview. As she does, another long-time activist named James Carlton admits he’s been listening in on our conversation.

“I was thinking,” he says, “PCR has never really taken the credit it should for being the oldest environmental justice organization in the United States — and opening other parts of the country’s eyes to environmental justice.”

Hazel Johnson passed away in 2011, but her legacy lives on. Her national and international impact endures in the way she enlightened the world on issues of environment, equity, and public health. Environmental justice issues have become mainstream in federal and local government, and central to the broader environmental movement. But for all this success, great challenges remain — most of all money.

“One of the biggest challenges was that the big environmental groups were getting all the attention. It’s still the whole perception of saving the whales and the trees, not talk about human health. Now, we’re addressing the real issue of equity,” Cheryl says. “Environmental groups like ours, for example, we are still grassroots, we’re still underfunded. How do we become totally funded, like Sierra Club, like the National Environmental Defense Fund?”

In the small office in Altgeld Gardens, Washington feels far away. But the newly gutted budget for the EPA can still affect communities like this one.

“We see some of our accomplishments being rolled back under this current administration, things we’ve been fighting for for many years,” Cheryl says. “Like with the Clean Air Act that President Obama put up. But I think it’s really forced us to look at things happening on a local level now, rather than on a federal.”

Hazel Johnson and the ‘Toxic Doughnut’ map. Credit: PCR

Hazel Johnson and the ‘Toxic Doughnut’ map. Credit: PCR

So, People for Community Recovery continues to monitor the neighborhood’s air quality. Members work with the Housing Authority to make Altgeld Gardens into a solar community, putting all the open space available to use in the name of sustainable energy and a toxin-free future. Another hope Cheryl shares with me before I leave is to make Carver Primary School — named after George Washington Carver, the botanist and inventor who developed techniques to improve soil depletion — into an environmental school. Environmental training programs already exist so that people from the area can get green jobs, and the hope is to build both a research center in the neighborhood and an Environmental Justice Museum with exhibitions about grassroots efforts all over the world. At the same time, the city of Chicago is planning to develop in Altgeld Gardens.

“They are proposing to put new structures out here like a new library, a new day-care center, and the new railroad; the CTA Red Line extension is going to come all the way down here,” Cheryl said. But of course, developments do not come without the threat of gentrification. Before the housing crash in 2008, plans to build waterfront property off the Little Calumet River were proposed. “I saw that plan and it was pretty,” she says. “But it wasn’t for our income level, it wasn’t for poor people. It was going to be a gated community.”

While PCR is often portrayed as only an environmental organization, the group also works with housing rights, helping clients receive fair and equal treatment in housing issues. “With all these opportunities coming to this area now, you just have to be on guard, the gatekeeper for your community. To make sure that it will still be here,” Cheryl says.

As I leave Altgeld Gardens, I pass the sign that declares the 2016 name change of the old South 130th Street. It’s now named “Hazel Johnson EJ Way.”

I stay in Chicago for a few days to hear Nigerian-American writer and critic Teju Cole read at the Museum of Contemporary Art, where Nigerian artist Otobong Nkanga has an exhibit. In his reading, Cole reflects on the time when his family moved to a less affluent area in Lagos, Nigeria, neighboring a roadworks plant that was spitting out black smoke: “For the next few years, that smoke was part of our life. There was no question of moving: this was the family house, the home we had built. But there was no real avenue of complaint either. The roadworks plant was run by a famous multinational company. Where would we begin? And thus did that black smoke come to rule our lives. It sprayed a grey on the washing on the line. It got into the tea. It smelled like burning tar or burning tires. It stung the eyes. It was, at the time, an inconvenience or irritation, an extra thing to clean away. Only now, in retrospect, do I understand how injurious it was and how intolerable it should’ve been.”

Environmental justice is an international phenomenon, linking the South Side of Chicago to other exploited communities across the globe. Cole’s father in Nigeria eventually got very sick from the dust in his lungs, but survived. On the far side of the Atlantic, in Chicago, Cheryl’s father was not so lucky. But Hazel Johnson did find it intolerable earlier than most people — and she did find avenues for her complaints, even though no path existed for her to follow.

In 1995, the tireless Mother of Environmental Justice told the Chicago Tribune: “Every day, I complain, protest, and object. But it takes such vigilance and activism to keep legislators on their toes and government accountable to the people on environmental issues. I’ve been thrown in jail twice for getting in the way of big business. But I don’t regret anything I’ve ever done, and I don’t think I’ll ever stop as long as I’m breathing. If we want a safe environment for our children and grandchildren, we must clean up our act, no matter how hard a task it might be.”

About the Author …

Lisen Holmström was born in Stockholm, Sweden, and is finishing up a M.S. degree in Landscape Ecology at the University of Illinois. This article was researched and written for ESE 498, the CEW capstone course, in Spring 2018.

Lisen Holmström was born in Stockholm, Sweden, and is finishing up a M.S. degree in Landscape Ecology at the University of Illinois. This article was researched and written for ESE 498, the CEW capstone course, in Spring 2018.